In mid of July 2013 Radiohead frontman Thom Yorke caused for controversies when he pulled his song catalogue and those of his band Atoms For Peace from music streaming service Spotify. His straight forward argument was as cited in The Guardian that “new artists get paid fuck all with this model”. Several artists take the same line as Yorke. The co-author of the Belinda Carlisle hit “Heaven is a Place on Earth”, Ellen Shipley, complained that the royalty paid by Pandora to her for more than 3m plays was US$ 40. She accused Pandora, Spotify, YouTube and Google for “(…) the meager, insulting, outrageous amount of money songwriters are being paid” according to Business Insider. In fact some big names are not available on Spotify: The Beatles, AC/DC, The Eagles, Garth Brooks, George Harrison.

Thus, the question arises if and how music streaming services can be valuable for artists? In the following I would like to highlight the pros and cons of music streaming services form an artists’ perspective.

Is Streaming the Next Big Thing? – The Artists’ Perspective

In a Pitchfork featured article Damon Krukowski of Galaxie 500 and Damon & Naomi fiercely attacked the music streaming services and breaks down the royalties being paid out to his band projects by them. For 13,760 plays of Galaxie 500’s “Tugboat” (initially released in 1988) on Pandora and Spotify the three songwriters received from US collecting society BMI US$ 1.26 in the first quarter of 2012 – 42 US cents each. Since Krukowski and his band mates also own the master rights of their recordings, Pandora paid a total of US$ 64.17 via digital collecting society SoundExchange for the use of the entire Galaxie 500 catalogue of 64 recordings to the three band members in the first quarter of 2012. Spotify, which has to license the rights directly from the rights-holders, negotiated a royalty rate of US$ 0.005 per play with the band’s record label. For 5,960 plays of “Tugboat”, Spotify would owe US$ 29.80 to the record label. Since the rate is adjusted for each stream for the frequency of play, the outlet that channelled the play to Spotify, the type of the users’ subscription etc., the label, however, was paid eventually US$ 9.18. This amount has to be shared with the three artists. Therefore Krukowski comes to the conclusion that “I have simply stopped looking to these business models to do anything for me financially as a musician.”

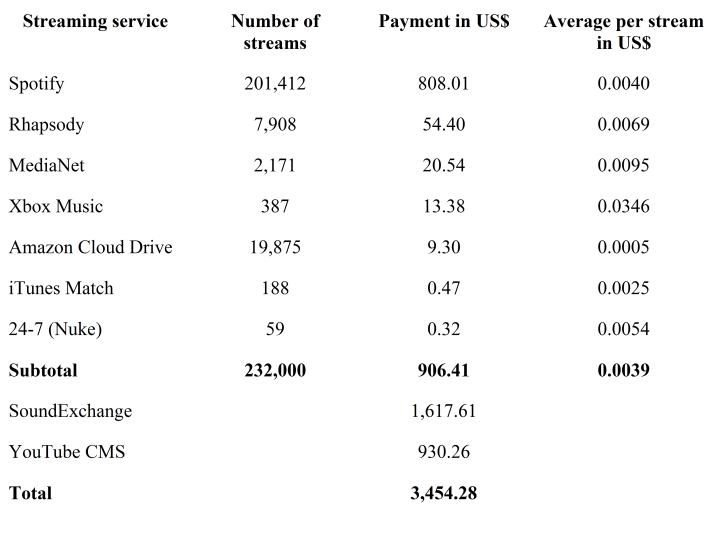

The cross-over cellist Zoë Keating comes to the same conclusion, but from a different standpoint. In a Guardian article she is cited: “I think Spotify is awesome as a listening platform. In my opinion artists should view it as a discovery service rather than a source of income.” Keating published the royalties received from streaming service for her solo albums “One Cello x 16” and “One Cello x 16: Natoma” in the first half of 2013 on Google Docs. For 232,000 streams she was paid US$ 906.41. Spotify contributed the lion’s share of US$ 808.01 for 201,412 plays.

Figure 1: Music Streaming Revenue for Zoë Keating in the first half of 2013

Figure 1 reveals not only that Spotify is by far the most important streaming revenue source for Zoë Keating, but also that its payments per stream (US$ 0.004) are below average. From an artist’s perspective the most valuable streams are made on Xbox Music, followed by MediaNet and Rhapsody. Streams on Amazon’s Cloud Drive, in contrast, are the least valuable (US$ 0.0005 per stream) ones.

In the Google Docs statistics, Zoë Keating also reports the revenue from SoundExchange (mainly Pandora) and YouTube Content Management System (CMS). In the first half of 2013, SoundExchange paid US$ 1,617.61 and YouTube US$ 930.26. Together with the revenue from “classical” streaming services, the half year’s income for Mrs. Keating from music streaming was US$ 3,454.28 or US$ 575.71 per month. This is comparatively high, but only a modest additional income for an artist such well-established than Zoë Keating.

A musician, therefore, needs 5.1m streams at a rate of 0.4 US cents to earn the federal US minimum wage of annually US$ 20,380 of a waiter/waitress.

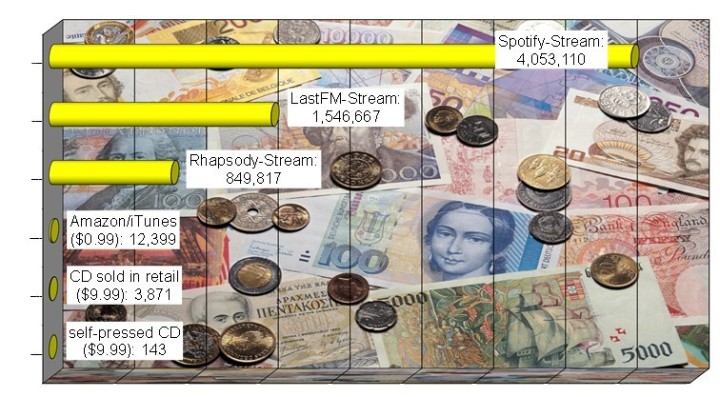

On TheCynicalMusician.com blog it was calculated that a musician in 2010 needed either 3,871 CDs sold in retail or 12,399 downloads on Amazon/iTunes or 4.05m Spotify streams to equal the then federal US minimum monthly wage of US$ 1,160.

Figure 2: The number of units sold to earn the US minimum wage in 2010

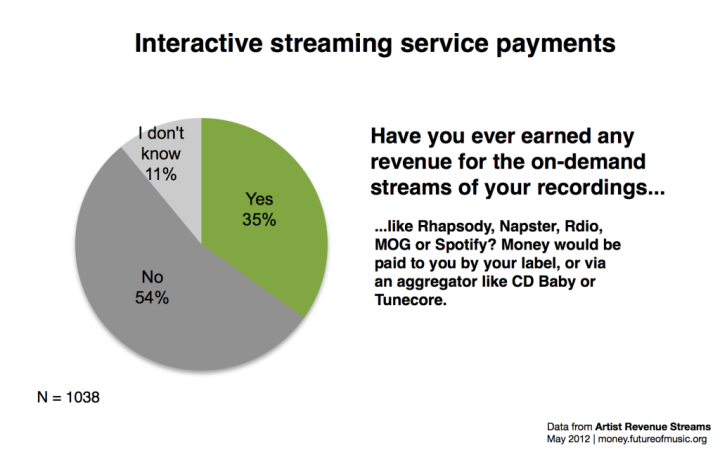

Although these cases give a first impression of the role streaming revenue plays for the total income of musicians, they do not provide an overall view. The “Artists Revenue Streams”-project of the “Future of Music Coalition” collected income data for 5,013 respondents – of a total of 7,395 people in an online survey conducted from September 6, 2011 to October, 28, 2011. Though the sample is not representative for the population of musicians in the U.S., the large size allows a good insight into the revenue situation of the survey participants. In the blog post “Off the Charts: Examining Musicians’ Income from Sound Recordings”, project manager Kristin Thomson presents survey data on revenues from music streaming and webcasting too. In a first step the survey respondents were asked whether they have ever received income from on-demand, interactive music subscription services like Rhapsody, rdio or Spotify. A minority of 35% (363 from 1,038) agreed (figure 3).

Figure 3: Interactive streaming service payments

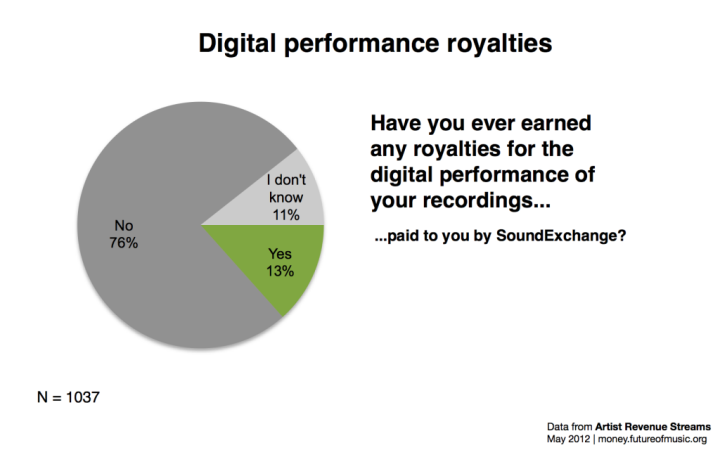

The same group of artists was asked if they ever received digital performance payments from SoundExcange for the use of the works in non-interactive Internet and satellite radios like Pandora, iHeartRadio or Slacker. Only 13% (135) agreed (figure 4).

Figure 4: Digital performance royalties paid by Sound Exchange

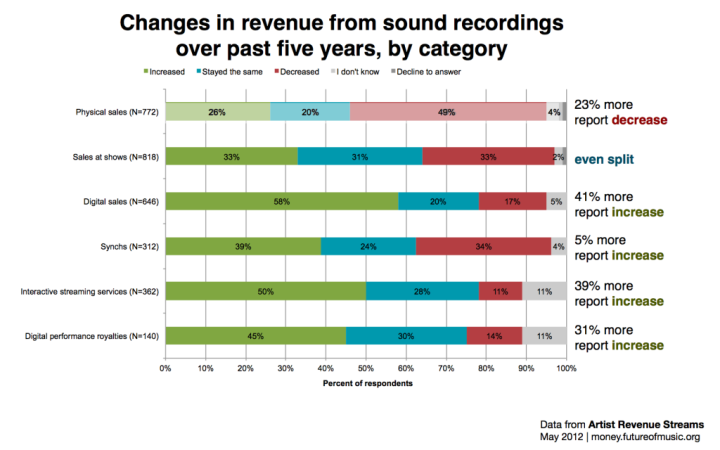

However, 51% of those artists who were paid royalties from streaming service reported an increase, whereas only 11% experienced a decrease in the past 5 years. Further 46% said that they get higher webcasting royalties from SoundExchange, whereas 14% reported that they earned less from Pandora & Co. In contrast, 49% of the respondents said that they got less from physical sales compared to 26% getting more (figure 5).

Figure 5: Changes in revenue from sound recordings, by category

These results reflect the shift from physical to digital sales. But that does not mean that digital sales can compensate for the loss of physical sales as one respondent pointed out in the survey: “though the revenue has increased, it has not increased proportionately compared to the ‘traditional’ or, what used to be, ‘conventional’ outlets where product could be sold. So this is not an accurate reflection of the total of ‘real sales’, comparatively speaking.”

Since the survey did not ask for absolute figures, we do not know how much U.S. artists earn from music streaming and webcasting. However, two financial case studies are presented in the blog post. They show that sound recording income, which also includes streaming and webcasting royalties – is in both cases negligible. The indie singer/songwriter earned 3.5% from recorded music sales in 2008-2011 and the jazz bandleader 1.7% in 2006-2011. The by far most important income sources for both were live performances (30.5% for the indie artist and 77.8% for the bandleader).

Thus, Kristin Thomson concludes “So, it’s pretty clear that the sources of income for sound recordings are shifting – away from brick and mortar and towards digital sales and, for some genres, sales at shows. Income from new sources [streaming and webcasting] is reported by a minority of survey respondents, but for those who have earned something, they say that it has grown over the past five years.”

Another source of information on the artists’ income from streaming and webcasting are the annual reports of US digital collecting society SoundExchange. SoundExchange collects the royalties from non-interactive Internet radios, webcasters and satellite radios such as Pandora, iHeartRadio, Slacker and Sirius XM and channels half of the money to the right holders (mainly record labels) and the other half to more than 90,000 artists (45% to interpreters and 5% to session musicians). According to the annual report 2012, SoundExchange collected US$ 507.3m and paid US$ 459.7m after administrative deductions to the right holders and artists. Thus, US$ 229.9m were paid to more than 90,000 artists. Each artists receives on average an annual payment of US$ 2,554. If we optimistically consider that 20% (18,000) of the artists got 80% of the webcasting royalties (US$ 183.9m), an “upper class” artist earns 10,218 on average, whereas the 80% “lower class” artists (72,000) get the rest of US$ 46m – US$ 639 on average per artist. It is clear that the payouts are insufficient to earn a living from webcasting royalties.

Conclusion

Music streaming and webcasting services currently are a negligible income source for the vast majority of artists. We have to distinguish, however, between interpreters, singer/songwriters and authors and it makes a difference if an artist or band owns her/his master and publishing rights or have given them away to labels and publishers. But also if the streaming market exponentially grows in the next few years, streaming and webcasting royalties will not compensate for losses of physical sales.

An artist should be realistic not to consider streaming royalties as a relevant income source. Nevertheless streaming platforms are important promotional tools for disseminating the music. In addition, they could be partners for artists to provide valuable data on user behaviour for tour planning and record releases. Zoë Keating, therefore, suggests in a blog post that digital music services should share more data with musicians to help them make money in other ways: “I wish I could make this demand: stream my music, but in exchange give me my listener data. But the law doesn’t give me that power. The law only demands I be paid in money, which at this point in my career is not as valuable as information. I’d rather be paid in data.” Thus, the most valuable asset for artists in the digital economy is access to data to monetize them by themselves.

Sources

Business Insider, “My Song ‘Heaven Is A Place On Earth’ Was Played More Than 3 Million Times On Pandora And I Was Paid Less Than $40”, July 8, 2013 (retrieved on September 19, 2013).

Keating Zoë, “What I want from Internet radio”, November 14, 2012 (retrieved on September, 26, 2013)

Pitchfork, “Making Cents” by Damon Krukowski, November 14, 2012 (retrieved on September 20, 2013)

TheCynicalMusician.com, “The Paradise That Should Have Been”, January 21, 2010 (retrieved on September 20, 2013)

SoundExchange, 2013, Annual report for 2012.

The Guardian, “Streaming music payments: how much do artists really receive?”, August 19, 2013 (retrieved on September 20, 2013).

The Guardian, “Thom Yorke blasts Spotify on Twitter as he pulls his music”, July 15, 2013 (retrieved on September 19, 2013).

In the 21st Century, professional music making is reserved to an elite. This elite is getting smaller each year. At this pace, professional musicians will be an extinct race in the near future.

Sort of depends on what your definition of “Professional” is? If you mean the mutli-millionaires living better then most people do, then yes. That era is finished. If you mean people who produce music but live comfortably as artist. Then no, they are not going away.

So musicians get paid less now from the physical sale of music..they were kinda over paid before. And, besides, they should be on their knees in thanks that these services have come along and pirating has gone down. They DEPEND on pandora, and spotify, and grooveshark, and torch music and all the other services that are at least paying them something.