The Joint Research Centre (JRC) of the EU Commission recently published a study entitled “Digital Music Consumption on the Internet: Evidence from Clickstream Data” with remarkable results. The authors, Luis Aguiar and Bertin Martens, concluded that music file sharing as well as music streaming have a significant positive impact on legal music downloads. The study is based on Clickstream data from Nielsen NetView. The database contains all the clicks of 25,000 Internet users in France, Germany, Italy, Spain and the United Kingdom for the calendar year 2011. In the following the main finding “(…) that digital music piracy does not displace legal music purchases in digital format” will be further investigated.

Data

Aguiar and Martens use Nielsen NetView data which were collected from representative panels of 25,000 Internet users in the five largest European countries – France, Germany, Italy, Spain and UK – for 2011. They classified three types of music consumptions sites on the web: file sharing networks (such as Torrents), music streaming portals (such as Spotify, Simfy, Deezer) and music download shops (such iTunes, Amazon Music). In total, the authors identified 2,759 music consumption related websites, which amounted to 5 million clicks during 2011. However, they restricted their sample to sites with more than 300 clicks per year. This results in a total number of 779 websites which were analysed in detail.

However, the method applied did not allow to observe precise consumer behaviour, but the number of clicks by the Internet users on music consumption sites. This also prevents to detect the music content of a download and stream. Thus, if the purchasing and non-purchasing clicks do not correlate, this would bias the statistical results. The authors realized this measurement problem and therefore states (FN 10, p. 7): „Since we do not expect the error component of our measure to be correlated with our measures of illegal downloading and legal streaming, the consistency of our estimates will not be affected“. Aguiar and Martens counter critical comments by the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry (IFPI) and journalists that they used the number of clicks on legal download platforms as dependent variables instead of the real purchase behaviour. The final measure of legal purchases would be larger, if they could include the clicks corresponding to legal downloads. In the words of the authors: “[O]ur current measure of legal digital music purchases is lower than the true one”. This also means that the real substitution effect of filesharing and streaming on legal download is weaker and the complementary effect is stronger than measured in the applied statistical model.

In contrast, the authors do not clearly address the problem to measure clicks on peer-to-peer file sharing services without differentiating between music, books and movies, whereas the later dominates the file sharing traffic. Nevertheless the authors believe that the number of clicks on file sharing sites is a useful proxy variable for downloading music for free.

Descriptive Statistics

Decriptive statistics show remarkable differences across the five investigated countries. Spain has the largest number of clicks on file sharing sites and the second lowest number of clicks on legal music websites – after Italy. Italy and the UK show also a larger number of clicks on file sharing networks compared to France and Germany.

Males are more active in purchasing, streaming and filesharing music than females, whereas the difference is largest in file sharing. It is less surprising that the under 30 years’ olds are the most intensive users of file sharing and streaming services. The most important age group in purchasing music are the 26-30 years’ olds, followed by the 41-50 years’ olds and the 31-40 years’ olds. The young generation (under 26) and the older generation (over 50) are less interested in purchasing music. Education, however, does not play any significant role whether music is consumed by file sharing, streaming and downloading. Households with a small and high annual income tend to stream music more often than households with an average income. As expected, the lower income groups prefer file sharing. It is remarkable, however, that low income households more often purchase music by downloading than middle and high income households.

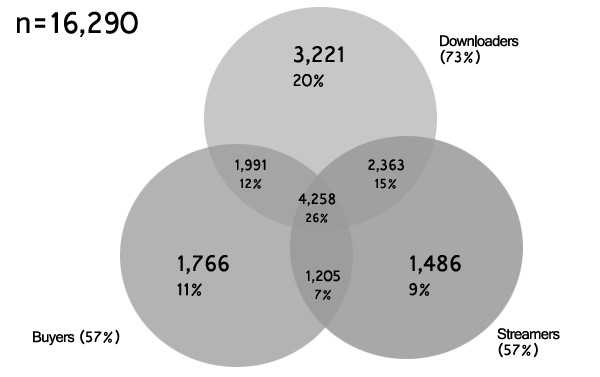

Another remarkable difference exists between regular file sharers music purchasers. The later are less active on the Internet (2.5 months per year) than file sharers, who are online 5.8 month per year on average. Thus, file sharers more often click on purchase sites (10% more often) and on streaming sites (40% more often) than non-file sharers. The difference between music streamers and non-streamers is very similar. Music streamers click twice as often on purchase sites than Internet users that do not stream music. This is again an evidence that file sharers use more often legal music download platforms and streaming services than non-file sharers. The cross correlation of the number of clicks on different music consumption channels can be seen in fig. 1:

Figure 1: Cross correlation of the number of clicks on legal download, file sharing and streaming websites

Source: digitalmusicnews.com, March 18, 2013.

Statistical Model and Empirical Results

There is need of a statistical model that partially controls for unobserved heterogeneity to measure the impact of file sharing and streaming on legal downloads. All three ways of music consumption are affected by an unobservable variable – musical taste. Thus, a direct measurement of the impact of filesharing and streaming on legal downloads is biased towards a positive correlation. To control for unobserved heterogeneity, the authors used clicks on music-related websites such as radio and music-video sites, but also music related sites without direct music consumption such as websites for songs’ lyrics, musical instruments, music news and music blogs. The statistical test shows that the vector composed of these variables significantly correlate with the independent variables – file sharing and streaming.

In controlling for unobserved heterogeneity more explanatory variables were added step by step. At the end the estimated coefficients show a small but positive impact of file sharing and streaming on digital music purchases. Both models, OLS and Tobit, came to similar results. In addition, a longitudinal approach is operated to overcome the obstacle that file sharing and streaming are endogenous. The results, thus, did not change fundamentally.

After all statistical methods applied, the model shows “(…) that illegal downloading and legal streaming have both a positive and significant effect on legal purchases of digital music” (p. 14). The calculated elasticities are 0.02 between file sharing and legal downloading and 0.07 between streaming and digital music purchases. This means that a 10% increase in clicks on file sharing sites leads to a 0.2% increase in clicks on legal music download sites. In the case of streaming a 10% increase results in a 0.7% increase in clicks on digital purchase websites (p. 1). In the absence of file sharing the clicks on legal download sites would be 2% lower.

The results show remarkable differences across countries, but the impact is always positive or at least not negative – such as in Spain and Italy. In France and UK the elasticity between file sharing and legal downloads is close to 0.04. Therefore, the authors conclude: “All of these results suggest that the vast majority of the music that is consumed illegally by the individuals in our sample would not have been legally purchased if illegal downloading websites were not available to them” (p.16). The results are valid ceteris paribus if no external influences such a changes in relative prices occur. The impact of streaming on digital music purchased also differ across the countries with elasticities of 0.6% in France and UK and 0.35% in Spain and Italy.

Finally the study comes to the conclusion: “[O]ur findings indicate that digital music piracy does not displace legal music purchases in digital format. This means that although there is trespassing of private property rights (copyrights), there is unlikely to be much harm done on digital music revenue.” The authors explicitly state that their findings cannot be generalized for the entire recorded music market (physical sound carriers included) and that the results contradict earlier research that found sales displacements of physical music sales by file sharing. The authors, however, conclude that “(…) music piracy should not be viewed as a growing concern for copyright holders in the digital era. In addition, or results indicate that new music consumption channels such as online streaming positively affect copyrights owners” (p. 17).

Critical Remarks

How reliable are the results of the study? It is problem that the number of clicks on music consumption websites were counted instead of measuring real digital music sales. Further it is questionable if the number of clicks is a good proxy for music consumption without considering the content. In the case of file sharing also other content than music was included in the sample. The authors try to circumvent the problems by using clicks on other music related websites as a proxy for music consumption. They argue that this also solves the problem of unobserved heterogeneity. As a statistical method this approach is legitimate. However, valuable qualitative information on music genres and musicians is lost. Therefore, it is for example impossible to differentiate between single and album sales. Maybe file sharing and streaming have a different impact on single track downloads and album download. It would also be possible that newcomers and less established artists are affected in a different way by file sharing and streaming than superstars. Although the authors could solve the problem of unobserved heterogeneity with the applied graduated statistical model, no qualitative conclusion could be drawn. The overall results, however, are valid a reliable.

Nevertheless an approach that tests the impact of file sharing by using log files and real streaming data on sale figures for digital music downloads would provide more insights into the relationship of different ways of music consumption. It is striking, however, that studies using this kind of method – Blackburn, Oberholzer-Gee/Strumpf and Tanaka – all came to the same conclusion that file sharing does not hurt music sales, which is more or less in line with findings of the JCR study.

Despite legitimate critique on the methodical approach of the JCR-study, the results show a weak but significant positive impact of file sharing and streaming on digital music sales. This should be seriously reflected by the artists and rights holders. A positive impact should be used for one’s own account instead of denying and refusing the results, since they do not fit in the usual thought patterns.

References

2 thoughts on “How Bad is Music File Sharing? – Part 25”